THINK TANK

India’s Tariff Hikes:

Weighing Costs Against Benefits

In an era of rising global trade barriers, India’s decision to hike tariffs on a wide range of imports will generate some pay-offs to industry, but will also exert large costs

Mounting protectionism globally is among the more striking features of the world economy. According to Global Trade Review, at least 467 ‘protectionist measures’ were imposed worldwide in 2017, including 90 in America alone and following on from 827 new measures levied the previous year. Donald Trump’s latest salvo – a big hike on steel and aluminium duties that may trigger a new global trade war – is part of a broader trend towards higher tariff- and non-tariff barriers in nation after nation. India is reacting similarly in a bid to protect its own industry, possibly give a fillip to ‘making in India’ and to shore up government revenues till GST stabilises. In the last one year, the Indian government - also in response to rising demand by industry bodies - has raised tariffs across a wide spectrum of products. Whilst this will aid viability in certain sectors and support sensitive interest groups like farmers, the flip sides are many and the path complex.

NOT ILLLEGAL…

73 per cent of all developing country non-agricultural imports are covered by the WTO’s bound rates, and India’s recent move does not violate this in any way

Going strictly by the book, India’s tariff hikes are permissible. Like other countries, and in line with its WTO commitments, it has over the years sharply reduced both its average and its maximum tariffs on most non-agricultural market access (NAMA) products. Indeed, 73 per cent of all developing-country NAMA imports are now covered by bound rates – the upper limit they are permitted to impose – up from 21 per cent in the pre-WTO days1. Staying within these bounds, the recent hikes do not violate any agreements. Agriculture, which is a sensitive sector for most countries, is largely outside this purview, which makes the recent big duty jumps in the processed-foods segment par for the course.

…AND WITH STRATEGIC INTENT

Agriculture, farmers and food processing – possible boost?

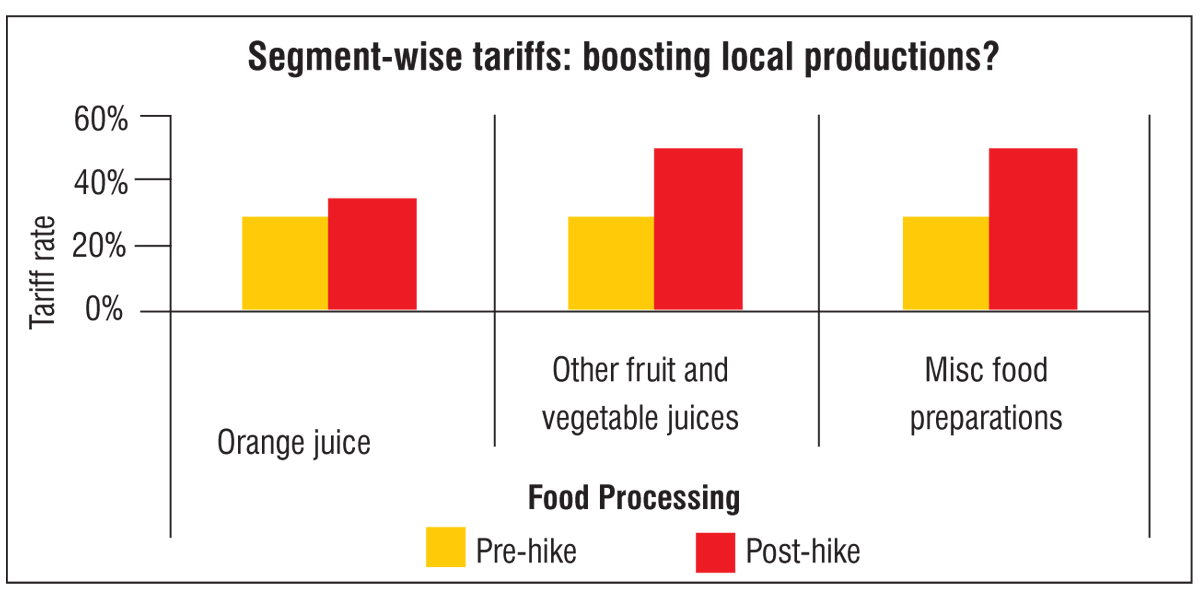

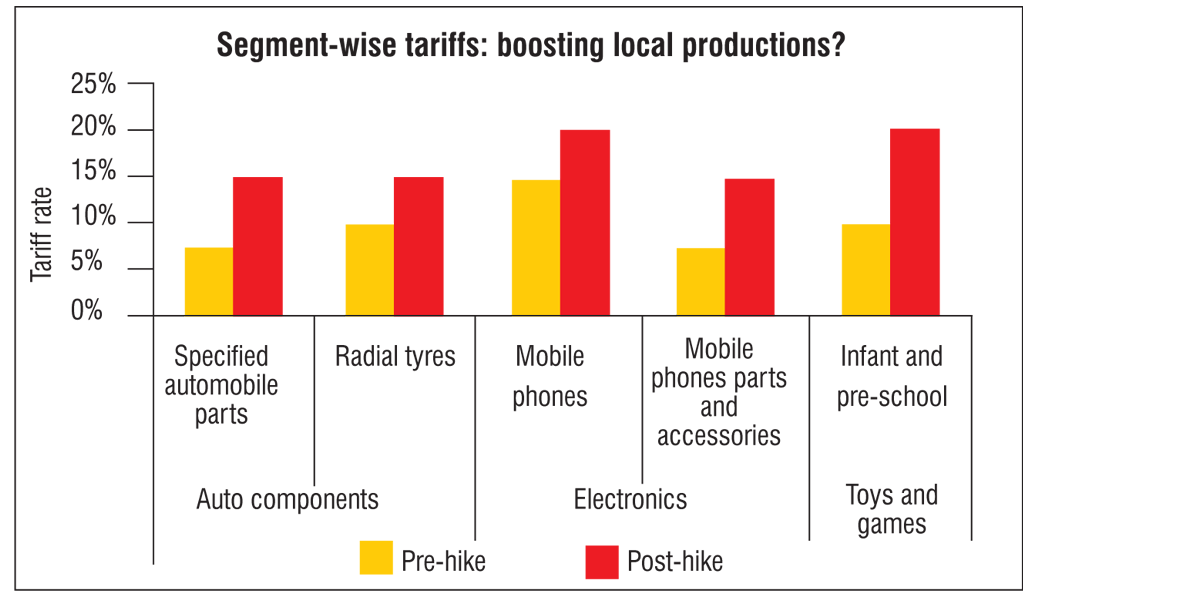

These decisions are a tightrope walk for the government. A close review of the tariff changes reveals two clear trends: the first is a bid to protect farmers and, in an environment of rising farmer distress (and a shift in the consumer food basket towards perishables like fruits and vegetables), to accelerate the food processing industry. In absolute terms, duties on fruit and vegetable juices, and on miscellaneous food preparations, have seen the biggest jump, from 30 per cent to 50 per cent for all categories (excluding orange juice, which went up from 30 per cent to 35 per cent). On the whole, this should incentivise local food processing – an industry valued at ~USD 40 billion in 2014 and forecast to grow to over USD 100 billion by 2025. With its massive potential for investment- and employment generation, a big duty hike will forcibly tilt the balance towards domestic production, especially given the Centre’s push for a ‘single market’. Indeed, last November, a number of large local and foreign companies made investment commitments totalling Rs 680 billion over the next 5 years, in everything from food production to supply chains.

The hike in tariffs of edible oil to the highest in over a decade is also a bid to support Indian farmers and Indian food processing. With 70 per cent of its requirements imported (up from 44 per cent in 2001-02), India is the world’s largest edible oil importer. Cheap imports from Indonesia, Malaysia, Brazil and Argentina are not possible for India’s oilseed crushers to compete against and have badly dented demand for local rapeseed and soybeans as well as palm and sunflower. In November 2017, India raised tariffs on imports of each of these. For example, it doubled the import tax on crude palm oil to 30 per cent (and again to 44 per cent with effect from March 1, 2018) and the duty on refined palm to 40 per cent from 25 per cent earlier. The import tax on crude soy-oil was increased to 30 per cent from 17.5 per cent (and to 35 per cent from 20 per cent on the refined version). Even as agricultural competitiveness sits at the heart of this challenge, tariff changes will, for now, stem imports to some degree in the immediate term. Demand is however, the real driver of import demand and in absence of dramatic change in agricultural practices and better market linkages, the end-result is likely to be higher inflation in edible oil. When the government took this call however, it may have been a calculated, balancing move bearing in mind almost stagnant inflation in this commodity across categories and the fact that farmers have sold produce 15-20 per cent lower than MSP. This is a complex arena however, with a variety of oils making up India’s edible oil mix including mustard, which has not seen the same support.

… also to local manufacturing in sectors of inherent capability…

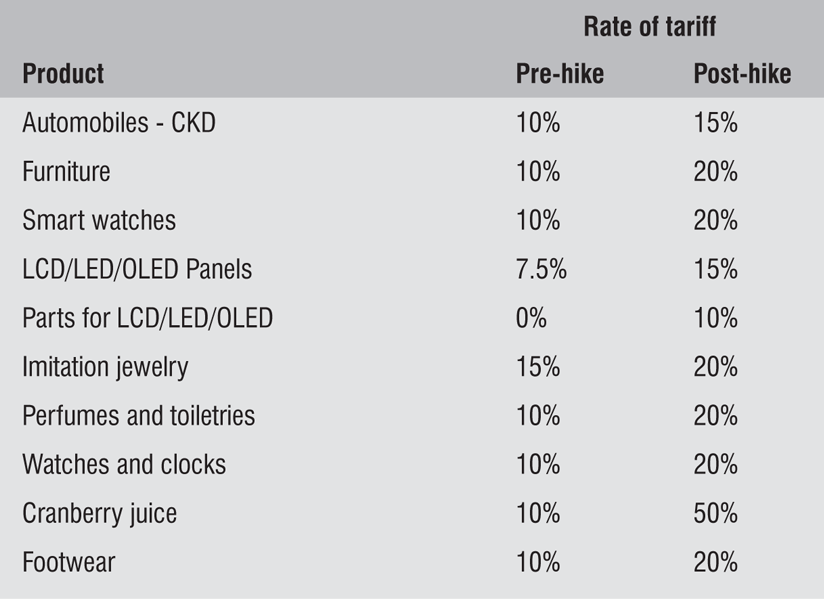

The second driver of India’s tariff hikes is a desire to aid local manufacturing. Illustratively, with duties on their products going up to 15 per cent from 7.5-10 per cent, auto component and bus/truck-tyre makers expect a spurt in investment, and a jump in capacity utilisation rates. Barring the most critical engine parts that go into luxury cars (which will continue to be imported), component makers also believe that the duty-hike will help them build scale and capacity, and ease the transition to the new BS-VI emission norms. In time, it may even erase or even reverse India’s small trade deficit – in FY17, it imported USD 13.5 billion and exported USD 10.9 billion – in auto components.

Electronics – over a tenth of all Indian imports by value (close on the heels of oil) – has also been in focus with customs duties going up across the board from mobile phones, video recording devices, electricity meters and digital cameras to microwave ovens, lamps and lighting fixtures. That said, the jury is a bit mixed on outcomes in this vast area. The case of mobile phone handsets is illustrative. Whilst customs duty has gone up by 5 per cent, that on printed circuit boards (PCBs) – ~55 per cent of the total value-add of a mobile phone – has not been touched. The incremental value-add of the duty hike then is likely to be modest2. It is also possible that the government is picking its battles, choosing those avenues where consumption is price inelastic (i.e. luxury goods), and where overall inflationary impact is modest.

Domestic manufacturing of luxury items in India is in any event, uncompetitive, given the small size of that market. At this juncture, no amount of protection will drive up the local value-add. Here, the only possible outcome of a duty hike is either higher end-prices, or – where demand is elastic – reduced consumption. At about 40,000 units a year, niche carmakers, for example, are unlikely to switch from the current, CKD-assembly model to full-fledged domestic production. Similarly, India cannot compete with established foreign brands – and in most cases, lacks the scale necessary to justify domestic manufacturing investments – in such segments as designer perfumes and toiletries; luxury watches, smart-watches and alarm clocks; or items like sunglasses and niche footwear.

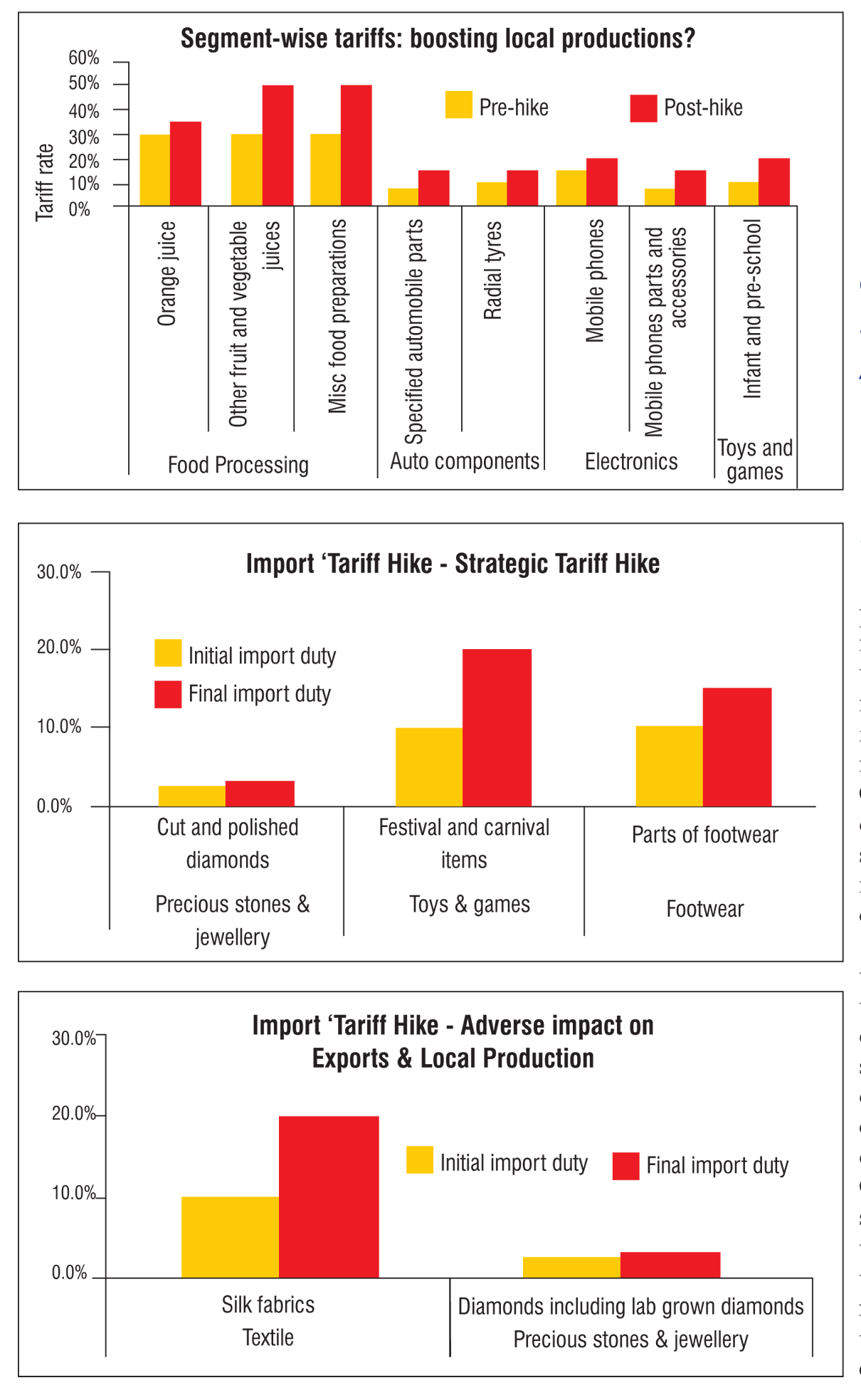

… with some prioritisation of other, more sustainable levers of competitiveness

In many sectors, these hikes are being complemented by the creation of over leavers. For example, toy-and-game makers and footwear companies – especially those whose principal markets lie outside the Tier-1/2 cities – will also have new and higher walls protecting them, both on account of duty hikes (which have gone up from 10 per cent to 20 per cent in both sectors), but also critically, other steps to promote local manufacturing. For one, new quality-testing standards for toys will make it difficult for cheap, sub-par Chinese imports to flood the market, raising import prices substantially. Over the next 2-3 years, this is likely to drive local toy manufacturing, particularly in the infant- and pre-school segments. Local footwear producers (concentrated in Agra) should expect a lift, too, from a recent, Rs 26 billion package for upgrading and modernising export units.

The risk of cross-purpose and the need for alignment

Tariffs have always been a double-edged sword. As an interim measure, particularly in an era of global protectionism, they go some way in giving a fillip to production. The risks lie in two areas – the first is in not linking tax policy to trade agreements. India’s FTAs, particularly with countries like Malaysia, Thailand and Bangladesh will offer the country many advantages with higher access to these markets and supply bases in line with India’s Act East policy. A critical disadvantage, however, is the fact of inherent higher competitiveness of production in many of these countries compared to India.

Bangladesh for example, is superbly competitive in textile manufacture. Under its FTAs with both India and China, even as garment manufacturers in India have to pay duty on imported fabrics, Bangladesh can import fabric from China duty-free, convert it into garments, and sell to India duty-free. And it does. The same applies for LED/OLED panels. With higher tariffs on these and a new tariff (10 per cent) on their parts, TV manufacturers like Sony and Samsung are reportedly considering scaling down their domestic assembly of TV panels, and instead importing readymade ones from countries like Thailand.

ALL SAID

The jury of the value of tariff protection then, is still out. Without question, the United States will see both rising complaints in the WTO against its tariff hikes and end results on domestic industry and inflation may be different than imagined. For example, the nation may gain a boost to domestic steel manufacture, but input costs – and end prices - will go up. If demand should fall, then the jobs at risk in end-user industries may well be much greater than those created in the manufacture of US steel and aluminium. India is no different. In the final analysis, our need for global competitiveness must be based on internal advantages in manufacturing in which both industry and government must invest. The government must continue to accelerate an enabling environment in financing, in the ease of doing business and by placing India in regional supply chains (India’s faster infrastructure development, very much a focus on the NDA government, is key to this). Agriculture is also a perfect case in point – without reform across production, land markets, irrigation and supply chains, dependence on imports will continue, as will India’s need for welfare subsidies. India’s poor record on storage is another illustration. Imports continue even when we have similar quantums in our granaries and other storage facilities simply because that quality is, simply put, largely inedible. On its own part, industry must continue to innovate on product and service, and build world standards in production rather than depending on government protection.

All said then, in the medium term, there is no better route to competitiveness than competitiveness itself – not supported by protectionism, but created by the relentless pursuit of excellence, and by the ability to compete on a level playing field. China’s scale-driven advantage in sectors like imitation jewellery or in the organised furniture sector relates to its own overwhelming capability now, not to government support that would have been the case earlier. Equally, openness to trade matters just as much, if not more, than the absolute size of a market, for investors into any country. However, in today’s mercantilist world, it may be unrealistic to expect any country to take the high road when easier, quicker options are at hand.

IMA India for CFO Connect