BIG PICTURE

GLOBAL OUTLOOK | REGIONAL OUTLOOK | INDIA OUTLOOK

Global Outlook

The IMF’s global growth forecasts are edging up, but slowing Asian exports are a warning sign

The Global and Regional Outlook is extracted from the Asia Pacific Executive Brief, a service of IMA ASIA.

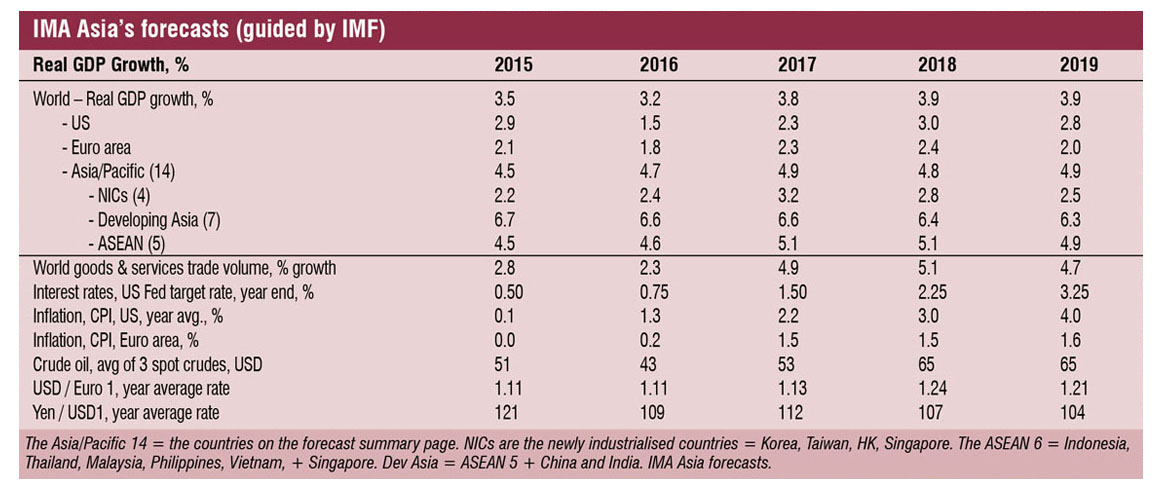

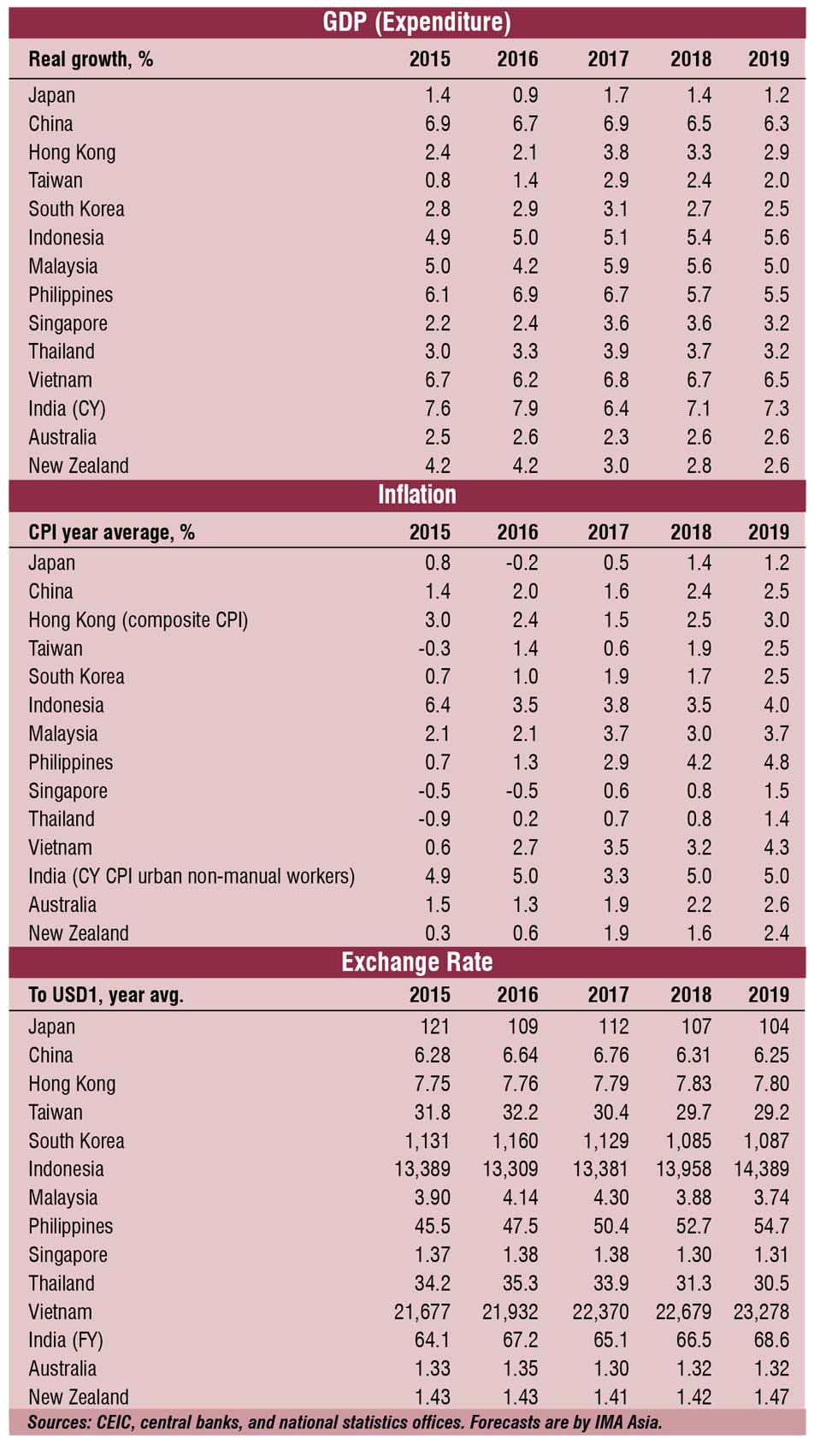

2017 turned out to be a good recovery year for the world, with growth lifting to 3.8 per cent, up from an average 3.5 per cent for the prior five years thanks to a synchronised upturn across the 40 biggest economies (all the advanced markets in the OECD and large emerging markets like China, India, Brazil and Russia). The result for Asia/Pacific was a jump in regional export growth to 10.7 per cent in 2017 from an average of -0.8 per centpa in the prior five years. In its April World Economic Outlook, the IMF nudged up its growth forecasts for 2018 and 2019 to 3.9 per cent for both years from a forecast of 3.7 per cent for both years made last October. There’s need for caution on the 2018 outlook, as early data for April suggests a slowdown in Asia’s export growth, which is a useful barometer for global demand. Still, the full year slowdown should be modest, with export growth in our forecasts of 7.5 per cent in 2018 and 5.0 per cent for 2019.

Two headwinds to watch are higher oil prices - likely to average USD 65/bbl in 2018 - and rising interest rates, with the US in particular moving steadily to end its massive QE programme

Support for firm global growth should come from the three big markets, which collectively accounted for 55 per cent of demand in 2017. In the US (24 per cent of world demand), Q1 growth eased to an annualised 2.3 per cent from 2.9 per cent in Q4’17, as consumers saved extra income from pay increases and tax cuts instead of spending it. Higher fuel prices could hurt middle class households, but there’s plenty of support for growth from a strong jobs market and the 100 per cent immediate depreciation for spending on plant and equipment. We expect US consumer growth to rise to 3 per cent this year from 2.8 per cent in 2017, followed by 2.4 per cent increase in 2019. Private fixed investment should grow 6-7 per cent this year from 4 per cent in 2017, with 4-6 per cent likely in 2019.

Growth in China (15 per cent of global demand in 2017) should also be good in 2018 and 2019. China demonstrated a remarkable ability for targeted stimulus in 2017, and we expect stimulus to be deployed in 2018 and 2018 if exports slump (due to trade wars) or its local demand cycle weakens. China PMIs just released for April show firm demand growth. The IMF expects the 2017 upturn in the Euro area (16 per cent of global demand in 2017) to continue in 2018 with 2.4 per cent growth before the pace cools to 2 per cent in 2019. While there’s plenty of concern about negative politics in Europe, the balance sheets for households, corporates and financial institutions have considerably improved and that should support growth.

The two headwinds that need watching are higher oil prices and rising interest rates. We’ve lifted our oil price assumption to US$65/bbl (avg of three main global crudes) from $55 during in 2017, which will hit consumer spending not just in the US but particularly in emerging markets. Global surplus oil stocks have been cut by Saudi Arabia and Russia trimming production and US frackers have run into pipeline constraints. As oil majors have also cut their exploration capex, higher oil prices are likely over the medium-term.

If you are confused about the interest rate direction and what that might be signalling, then join the club. The big picture is an end to 5-8 years of quantitative easing (QE) and a slow lift in interest rates from record lows. The US is heading down this path, with justification from local inflation numbers, but almost no one else is. Moreover, the yield curve between the 2-year and 10-year US bonds is close to flat, which usually means that a slump in growth lies ahead. At present, we simply deduce that volatility will rise as QE ends and that the weaker emerging markets will suffer capital outflows, and both happened in Q1’18.

With the US Fed expected to lift its policy rate three times this year the recent slide in the US$ has stopped and the currency is set for a return to appreciation in 2018 and 2019.

Regional Outlook

Geopolitical risk is easing in North Asia, while Xi Jinping is pushing ahead with tough reforms

Milder export growth aside, energy-intensive Asia will confront the threat of higher oil prices, spurring bigger trade deficits for India, Indonesia, and the Philippines, and weaker demand in several countries

North Korea’s rapprochement with China and South Korea, and possibly within months with the US and Japan, will not lead to Pyongyang giving up its nuclear weapons, or to the US withdrawing its forces from South Korea, or to a path that culminates in re-unification. However, it should ease geopolitical risk in North Asia, both for South Korea and for US firms in China who would be collaterally damaged by any hostilities between the US and North Korea. President Kim Jong-un is moving from the risk-raising phase of his strategy, which has achieved three great victories (long-range nuclear capacity, international acceptance as a nuclear power, and bringing the US president to the negotiating table) to a risk-lowering phase (get embargoes and sanctions lifted and, possibly, signing a peace treaty with the US). That should secure the position of the North Korean regime, allow President Trump to declare a “tremendous victory”, and be acceptable to China and Japan.

Between the 19th Communist Party Congress last October and the first session of the 13th National People’s Congress in March, China carried out a major restructuring of its political and administrative processes. The changes should help China lower various types of risk (ranging from leadership battles to a financial crisis), while also allowing it to push forward with tough reforms that will underpin another decade of strong growth. That’s a plus for the rest of Asia, as good China demand helps all of China’s neighbours.

A key question in early 2018 was whether we’d underestimated the strength of global demand this year, just as we’d underestimated the strength of the export recovery in 2017. However, the latest data suggests that global demand growth is cooling, which has been our main assumption. Early data reporters Vietnam and South Korea have announced weak US$-based exports for April (4.1 per cent yoy and -1.5 per cent yoy from 25.1 per cent yoy and 10.1 per cent yoy respectively in Q1’18). Vietnam’s exports surged 21.4 per cent in 2017, while Korea’s exports were up 15.8 per cent. For Asia/Pacific as a whole, we expect export growth (US$ basis) of about 7 per cent this year and 5 per cent in 2019 after 11 per cent growth in 2017. That’s still sufficient to give a positive export kick to growth. Growth in industrial production will slow, but should find support at about half the pace of 2017 with help from steady domestic demand growth in most countries. Good local demand accounts for a lift in GDP real growth for the 14 A/P countries to 4.8 per cent this year and in 2019 from 4.7 per cent in 2016 and 4.5 per cent in 2015.

Apart from milder export growth, Asia will also confront higher oil prices, which is a major threat, as Asia’s fast growth is energy intensive. Higher oil prices will lead to bigger trade deficits for India, Indonesia, and the Philippines, and weaker demand from low-income households in India and all ASEAN countries bar Singapore. In response, governments in Thailand and Indonesia have recently imposed caps on fuel price rises. While that’s bad for the profits of fuel distributors and undermines sound policy, it will help consumers in the short-term. Provided oil doesn’t breach $80/bbl, the negative impact should be mild.

A lift in fixed investment will also be part of Asia’s domestic demand story in Japan, Korea, Taiwan, Indonesia, Singapore, and Thailand. Strong, but slightly slower capex growth is expected in China, HK, Malaysia, Philippines, Vietnam, India, Australia and NZ. Central banks in most of these countries will lag the US Fed’s rate lifting cycle, as they aim to encourage local demand growth and stop local currencies rising on a weak US$.

Only three countries stand out for macro risk as the global economy moves to mildly tighter monetary policy – the Philippines, India, and Indonesia. All three will run higher inflation while India and the Philippines run bigger trade deficits and Indonesia’s trade surplus shrinks. While Moody’s has just upgraded Indonesia’s sovereign rating (to Baa2 – two notches into investment grade), that hasn’t stopped capital leaving and the Rupiah falling.

As we expect the US$ to return to a mild strengthening on its trade weighted index over the rest of this year, most of Asia will aim for much slower appreciation on the greenback.

However, three currencies – India’s Rupee, the Indonesian Rupiah, and the Philippines Peso - face downside risk, as the underlying economies have elevated macro risk at the same time as global markets shy away from riskier emerging market currencies.

Richard Martin is Managing Director, IMA Asia. He can be reached at richard.martin@imaasia.com

India Outlook

A crucial Assembly election in Karnataka will set the tone for the months ahead

Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s BJP-led government has served almost four years of its first 5-year term and seeks a second term in 2019. Its main opponent, the Congress Party, is weak by itself but hoping to cobble together a coalition that could help put up a better fight. A bigger issue is when the BJP will gain control of the 245-seat upper house, where many of its bills have been blocked previously. Seats in that house are determined by India’s state legislatures, and it is here that India’s political landscape is shifting. A string of state assembly poll wins has put the BJP or its allies in power in 21 of India’s 35 states and territories, the highest score ever achieved in India’s history. As upper house MPs serve out 6-year terms with one third retiring every two years, that swing in power will only happen over time. The BJP on its own will not reach upper house majority until 2020 but it has acquired enough strength to at least obtain issue-based victories. It currently has 69 seats, while its NDA coalition has 86 seats after biennial upper house polls in March. Opposition parties control another 103 leaving 52 members across multiple minor parties that the BJP can try to negotiate with on a bill-by-bill basis.

GDP growth rebounded in Oct-Dec, and both investment and consumer demand are picking up

Assembly polls in three north-eastern states in March highlight the swing to the BJP. In Tripura, the BJP trounced Congress and the incumbent Left front to win 43 out of 59 seats. In Nagaland, its coalition NDPP won 29 out of 60 seats, while in Meghalaya it partnered the winning NPP coalition. Historically, the BJP has been non-existent in the three states. Its wins reflect popular support for Mr Modi’s promise of reform-driven growth as well as the organisational skills of BJP Party President Amit Shah. Yet, March also saw the Telugu Desam Party (TDP) leave the BJP-led coalition after its demand for special treatment for its state of Andhra Pradesh was rejected by the BJP as unconstitutional.

For now, the focus is on assembly elections in Karnataka next week where the incumbent Congress seeks to retain one of only four states under its fold. For the BJP a victory would a big confidence-builder as it has historically been weak in South India whereas for the latter it is almost a question of survival. The election is scheduled on May 12 with results to be declared on May 15.

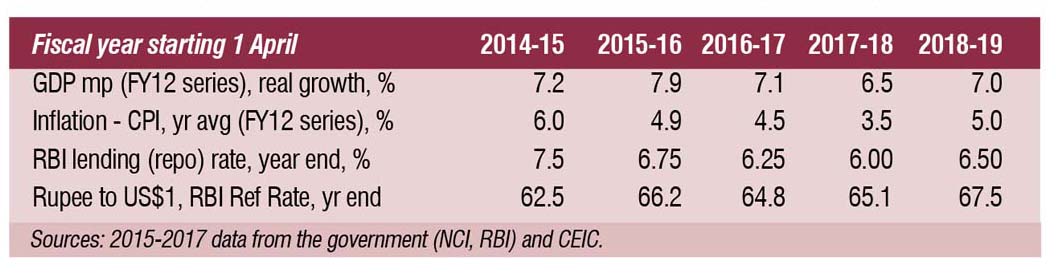

Underlying growth picked up faster than expected in the December quarter with GDP expenditure lifting by 7.2 per cent yoy from 6.1 per cent ytd in the first three quarters of calendar 2017. The big gain was in fixed investment, which surged 12 per cent yoy after a gain of just 4.8 per cent ytd in the first three quarters. Full year GDP (expenditure) growth was 6.4 per cent , with fixed investment up 6.6 per cent (slowing from 10.5 per cent in 2016) and consumer demand up 5.7 per cent (slowing from 8.3 per cent in 2016). As the factors that slowed domestic demand growth in 2017 (demonetisation and GST) fade, GDP growth should lift above 7 per cent in 2018 and 2019.

The investment surge is reflected in strong rebounds in the industrial production indices for cement (up 11.4 per cent ytd in the December quarter from a 5-year average quarterly rate of 3.3 per cent ) and steel (up 9 per cent yoy from a 5-year average quarterly rate of 5.6 per cent ). That matched a recovery in construction GDP, up 6.8 per cent yoy after no growth in the first three quarters of calendar 2017. For 2018 and 2019, we expect construction growth to lift to 4-5 per cent from 1.8 per cent in 2017 and a 5-year average to 2016 of 3.4 per cent. That should help lift overall investment growth to 7-8 per cent over the next two years from 6.6 per cent in 2017.

India’s rupee is at risk in 2018 and 2019 from the combination of higher inflation and trade deficits and an end to net quantitative easing by advanced markets. After a 3.2 per cent rise in 2017 on the US$, we expect the Rupee to fall 1-3 per cent pa in 2018-19.

India’s economy has accelerated over the last couple of quarters with GDP growth rising to 7.2 per cent between October and December.

India’s economy has accelerated over the last couple of quarters with GDP growth rising to 7.2 per cent between October and December. Pushpa Nair explores the land of trumpet, roar and song

Pushpa Nair explores the land of trumpet, roar and song