THINK TANK

The Indian Insurance Sector:

Shining Again?

Economic growth, favourable demographics, robust public policy and – especially – technological change are spurring a revival of insurance in India

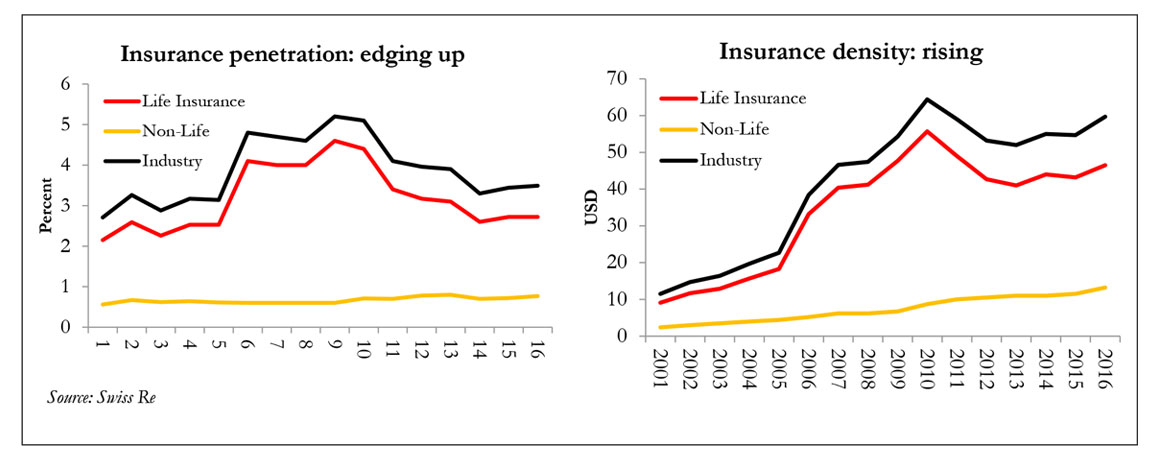

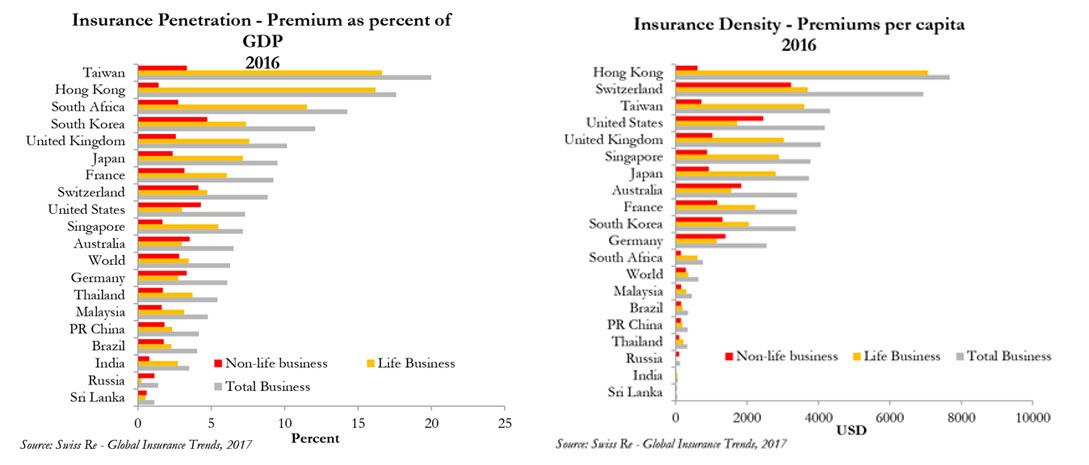

Considered one of India’s sunrise industries in the early 2000s, insurance fell on hard times after the GFC. Today, though, revival beckons, driven by demographics and rising incomes on the one end and sound regulation and a public policy thrust at the other. Penetration levels (premiums as a share of GDP) remain low – just 2.7 per cent in life insurance – which implies considerable growth potential, given a young, upwardly mobile population.

From its high water mark in 2009-10, insurance penetration and density both fell, but they are now on the rise again

More liberal FDI norms, easier regulations around distribution and an infusion of public money, will drive the expansion of the industry in the medium-term. Digital technologies could be additional enablers, helping tackle some of the industry’s main constraints such as high costs, low levels of customer engagement and limited customisation. For a sector whose fortunes are intimately linked with economic development and income-security, that is good news.FROM BOOM TO BUST…

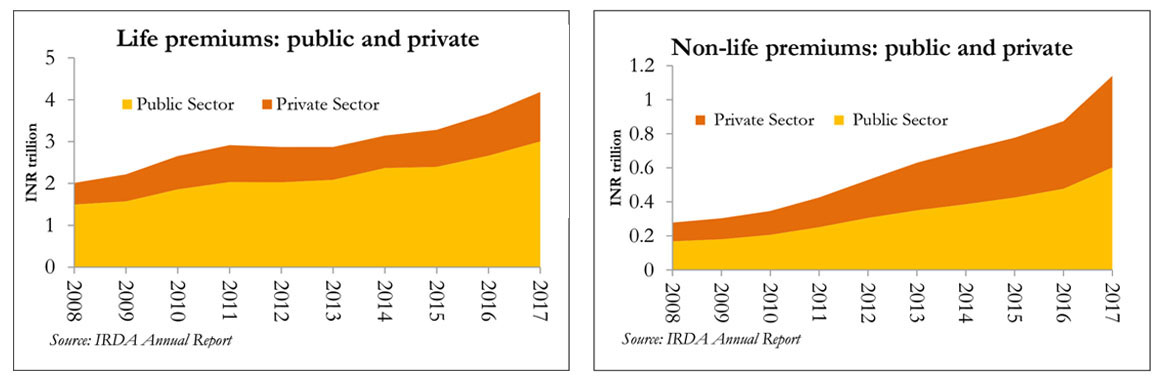

2009-10 was a high water mark for the insurance sector. Between 2001 and 2010, insurance density – i.e. per-capita premiums – leaped six-fold, from ~USD 10 to over USD 60. Meanwhile, from a lowly ~2 per cent in 2001, life-insurance penetration peaked at over 4 per cent in 2009 (including non-life, the figure was 5.2 per cent), but then dropped back down almost as sharply. Unit linked insurance plans (ULIPs) were at the heart of these movements, in both directions. Exorbitant commissions – 50-100 per cent of first-year premiums – meant that they were (mis)sold en masse, while prohibitive exit penalties (typically 100 per cent) propped up renewal rates. The GFC, though, sent fund-values – and therefore investor confidence – crashing. Around the same time, a regulatory clampdown made it cheaper for investors to surrender ULIPs, while a cap on commissions (5-8 per cent, depending on the insurer’s expense ratio) did away with the incentive to over-sell these products. Tellingly, LIC sold over 10 million ULIPs in FY10, but just 1.5 million two years later. From 80-90 per cent of the industry-wide life premiums, ULIPs now generate a more modest 40-50 per cent – and for the sole PSU life insurer, LIC, just 3 per cent.

ON AN UPWARD TRAJECTORY AGAIN

More recently, both of these ‘success markers’ have been edging up, driven by a mix of macro-climatic and policy factors. An increasingly young, better educated, better paid workforce – and one that is shifting to formal wage employment – is starting to prioritise insurance cover. Just as important, with life expectancy rising, the total insurable population will swell to an estimated 750 million people in 2020. The life insurance industry expects its top line to continue growing at 20-25 per cent rates, crossing USD 100 billion in 2020. The NDA government’s push for a comprehensive social-security net is also making a difference and even among the poorest families, insurance is getting embedded into people’s daily lives. The Pradhan Mantri Jeevan Jyoti Bima Yojana (PMJJBY) and Pradhan Mantri Suraksha Bima Yojana (PMJSBY) schemes provide free or nominal-cost (less than Rs 1/day) life and accident cover to the poor. Over 100 million people enrolled in just the first year and their recent extension to the entire BPL (below poverty line) population will bump the numbers up quickly. Moreover, ultra-cheap air- and rail-travel cover – the railways offer a coverage of Rs 1 million for just 92 paise (free until August 31st) – can now be purchased at the click of a button while booking tickets online, and many are opting to do so. On the non-life side of the equation, the Rs 500,000-per-family National Health Protection Scheme (NHPS) will be a game-changer, bringing 100 million families under insurance coverage, many for the first time. More broadly, the rising formalisation and ‘financialisation’ of India, including through the Jan Dhan Yojana, the GST, Aadhar-eKYC linkages and so on, is making financial products more attractive and easier to buy.

EASING DISTRIBUTION, INFUSING NEW MONEY

The NDA’s push for a comprehensive social-security net is making a difference, as is its more general drive towards greater formalisation and ‘financialisation’

Three additional structural factors are at play. First, a 2016 change in the bancassurance rules allow banks to now market the products of up to three life and three non-life insurance companies – up from one each previously – as well as three standalone health insurers. This ‘open architecture’ model vastly expands the available distribution channels – and PSU banks, with their deeper reach, may be instrumental in pushing up penetration rates in the years ahead. (On the flip side, this also increases banks’ potential liability around forced- or mis-selling charges.) Second, the 2015 amendment of the Insurance Act, which allowed for a higher, 49 per cent cap on FDI (up from 26 per cent) has spurred shareholding changes – AXA, Bupa, Nippon, Ergo, Standard and Sunlife, for instance, have all raised their JV stakes – and is likely to drive further, capacity-enhancing investments in the years ahead. A recent government proposal to allow 100 per cent FDI in insurance broking will, if accepted, bring new investments into a critically-important distribution channel, pushing up both penetration and density. Third, although insurance companies are no longer compelled, as they were until 2015, to compulsorily list themselves after 10 years of operations, many have chosen to do so – with the last year seeing a wave of IPOs, if not wholly successful ones. Together with the government’s recent decision to merge three of India’s four PSU general insurance firms, this will mean deeper pockets and greater transparency for the insurance sector, which should eventually drive up coverage as well. Industry insiders believe that a wave of consolidation is not far off, and if that comes to pass, there will be fewer but bigger and more competitive firms left in the field, better positioned to expand the sector.

DIGITAL: PUSHING THE BOUNDARIES

Arguably, it is digital technologies that will give the greatest fillip to growth – especially in the non-life segment, which is under-penetrated relative to life insurance. Compared to a global average of 45 per cent, in India, general insurance accounts for just 22 per cent of industry revenue. Digital channels – including email, website, search-engine integration and tele-assist – have, together with more robust payments systems and Aadhar-based authentication, removed much of the friction around purchasing and renewing policies, or making claims. Motor insurance claims of under Rs 20,000 can now be processed instantly, using a smartphone. Travel insurance can be purchased quickly online, as can several types of medical and other insurance. What lies ahead are even bigger, potentially tectonic shifts. A mix of big data analytics, blockchain technologies, machine learning, automation and artificial intelligence – aided by a proliferation of Internet-of-Things (IoT) devices – will, in time, help tackle some of the industry’s biggest constraints: high costs, low persistency (i.e. renewal) ratios, low levels of customer engagement and limited personalisation. More insurance agents now carry ‘connected’ tablets, speeding up sales and other transactions. By driving up productivity, this improves individual earnings which helps keep down attrition. Given the high cost of recruiting and training agents, this can make a big difference to the bottom line. Analytics, IoT and blockchain will also, in the next few years, enable claims-processing efficiencies and reduce fraud, again cutting into cost.

Bancassurance rules have been liberalised, FDI caps have been raised, and a wave of IPOs has generated huge amounts of cash

Customer engagement and personalisation are huge imperatives for insurers – and technology will make a difference there, too. Surveys find that insurance ranks lower than almost any other service sector in terms of customer connect, with limited touch points and high levels of intermediation. Digital can take care of both these issues by cutting out the intermediary (chat-bots can answer many routine questions) and by tapping into reams of information – from financial and life-stage data to social media presence – to create context-aware, micro-segmented, highly personalised interactions. Analytics can predict, for example, the likelihood of someone not renewing their policy, allowing the insurer to take action before it is too late. Other data points might alert the firm, say, if a person has just moved to a bigger home, started a family or is about to travel abroad. They can then be sold tailored offerings – for instance, home insurance that covers only the duration of the holiday. With IoT enablement, motor insurance can move to a ‘pay as you drive’ pricing model (which depends on the number of kilometres driven in a year) or even to one that is ‘pay how you drive’ (which factors in things like sudden acceleration or braking, whether the car is properly maintained, and so on). Wearable devices may soon allow health insurance premiums to be set more precisely – and fairly.

WATCH OUT FOR THE DARK CLOUDS

WATCH OUT FOR THE DARK CLOUDS

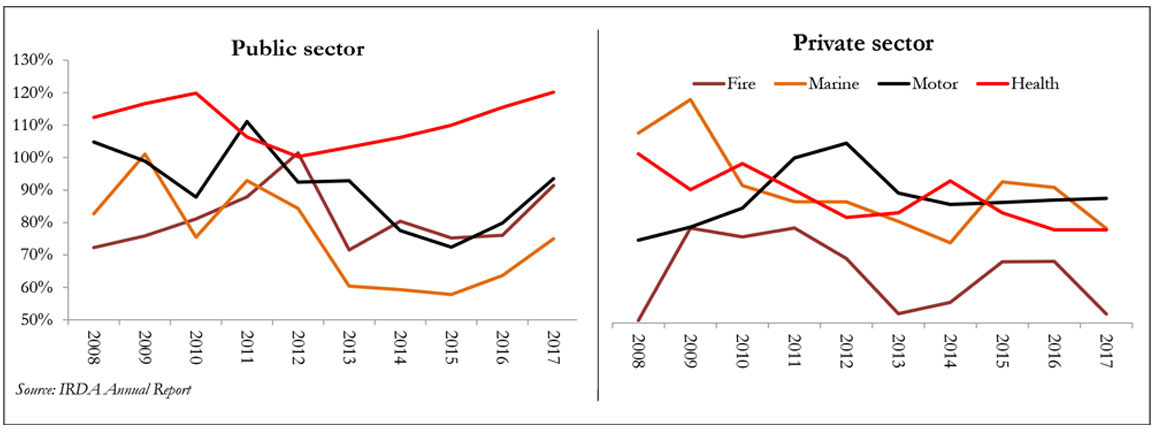

All said, the sun appears to be shining again on the insurance sector, even if there are challenges to contend with – not least the inevitable disruptions that technological change will bring. PSU insurers, particularly in the general insurance segment, will also have to watch out for claims ratios slipping out of hand.

Technology will help tackle some of the industry’s biggest constraints: high costs, low persistency ratios, low levels of customer engagement and limited personalisation

Compared to their private-sector peers, PSUs have suffered continuing underwriting losses – partly because stiff competition has driven them to bring down prices to unsustainable levels. Their claims ratios, already far from healthy, are rising, especially in the health insurance segment, where it routinely exceeds 100 per cent, compared to below 80 per cent for the private sector. As the ‘Modicare’ scheme takes root, PSUs will presumably get most of this new business (the details are still being hashed out), but also the lion’s share of the liabilities. Adverse selection – poorer households are likelier to make bigger claims, more often – will be a major risk. Even if it does not block out the sun entirely, it will bring with it a few dark clouds.IMA India for CFO Connect

India’s economy has accelerated over the last couple of quarters with GDP growth rising to 7.2 per cent between October and December.

India’s economy has accelerated over the last couple of quarters with GDP growth rising to 7.2 per cent between October and December. Pushpa Nair explores the land of trumpet, roar and song

Pushpa Nair explores the land of trumpet, roar and song