BIG PICTURE

GLOBAL OUTLOOK | REGIONAL OUTLOOK | INDIA OUTLOOK

Global growth has had a strong start this year, but populism and the winding down of QE present risks

The Global and Regional Outlook is extracted from the Asia Pacific Executive Brief, a service of IMA ASIA.

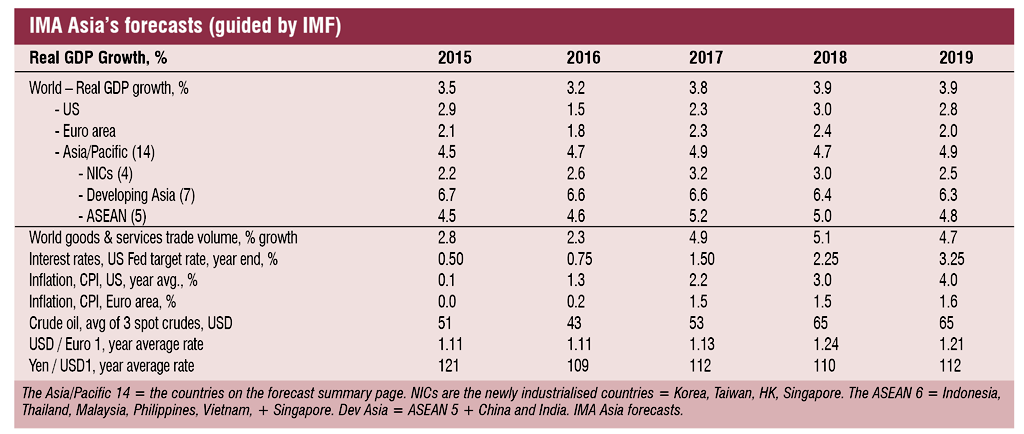

The global economy had a strong start to 2018 according to our favourite measure. Exports for the A/P14 covered by the Asia Brief grew 11.7%yoy in Q1’18 followed by 10.9%yoy in April, which is in line with full 2017 growth of 10.7%. Keep in mind that’s after five straight years when A/P14 exports fell by an average 0.8%pa. As Asia makes a lot of the world’s goods, this measuring stick suggests sustained strong demand in Q1’18 after the 2017 recovery. That recovery reflected healthier balance sheets in Europe, China, and the US. In its April forecast, the IMF put global growth at 3.9% this year and in 2019, from 3.8% in 2017 and a decade average of 3.5%pa to 2016. Despite all the risks, that remains a reasonable forecast, as most risks are less bothersome if a market has momentum.

Trump’s tax cuts, particularly immediate 100% depreciation for capex, has given the US recovery a second wind. GDP growth lifted to 2.9%yoy in Q1’18 from 2.3% for full 2017. That was led by a 4.6% rise in private fixed investment from 4% growth in 2017. We expect private capex to grow by 6.8% this year and 5% next year. Consumers were slower off the mark with 2.6%yoy growth in Q1’18 down from 2.8% for full 2017. The boost from income tax cuts and strong employment growth was likely offset by a jump in fuel prices and weak wage growth. Overall, we expect 3% GDP growth this year and 2.8% in 2019 after 2.3% growth in 2017 and a decade average of 1.4%pa to 2016. Euro zone growth edged up to 2.5%yoy in Q1’18 from 2.3% in 2017. While the zone has yet to break out its Q1 GDP data, most indicators point to broad growth. Imports and exports for March were both up 17%yoy (US$ terms, our standard cross-country measure), while industrial production was up 3%yoy after 2.9% growth in full 2017. Unemployment in March was down to 7.1% from 7.9% a year earlier, while growth in the annual rate for new car sales edged up to 6%yoy in March from 5.7%yoy in December 2017. The IMF puts GDP real growth this year slightly up on 2017 at 2.4% before it eases to 2% next year. That’s well above the decade average to 2016 of 0.7%pa.

US growth has got a second wind from Donald Trump’s tax cuts, Asian exports are on an upward track, and the Euro zone is seeing broad growth

While good growth will help mitigate risks two challenges need watching. The first is a gradual exit from quantitative easing (QE). The US and England have stopped it, and China is curbing the wilder fringes of its credit growth. The Euro zone is likely to stop its QE by the end of this year, which leaves Japan alone continuing QE into 2019. That has a big impact by reversing the flow of ultra-cheap capital into risky assets (either emerging markets like Argentina or Turkey or bubbly real estate markets). In Asia, that puts India, Indonesia, and the Philippines on a watch list for currency falls, while HK’s soaring property prices are a worry. It also means the end of cheap working capital in corporate supply chains, as our May CFO meeting in Singapore explored.

The second risk is the rise of populist politicians and protectionist trade and industry policies. It has already delivered the shocks of Brexit and a Trump presidency, both of which will have an impact on markets. While political grandstanding and damage to specific firms gains press attention, fundamental adjustments will likely be needed to long-term strategy (indeed, the protectionists aim for that).

Combine strong US growth and rising interest rates with milder growth and low policy rates in other OECD economies and rising global market volatility and you have a recipe for a big rise in the US$.

Asian domestic demand remains strong, but India, Indonesia and the Philippines face rising currency risks

One of the wonderful things about democracy is the way that voters can overturn prevailing wisdom, as they did in Malaysia in May by dumping a 62-year old government that had looked certain to win. We have a lot to learn about the new government led by a politically reborn Dr Mahathir, ranging from a change in policy on big projects to a questionable deal to hand power to Anwar Ibrahim in two years. But already we can see a swing in drivers from growth led by big projects (and China) to a lift in consumer demand and sentiment after the GST was zeroed on June 1. The military in Thailand is toying with plans for its own tightly controlled election in 2019 and will have been shocked by the Malaysian poll. Does money, coercion, and gerrymandering count for so little today?

Despite conflicting reports of progress and failure on US-China trade talks, and an avalanche of “what-if” analysis, one underlying theme is emerging. Economic nationalism is on the rise, particularly in the US and China, and companies will need to adapt their strategy. At one extreme that may mean choosing which camp to belong to, although most firms will try strategies that can bridge the growing divide. That likely means big adjustments to supply chains, which might be a boost for production in Taiwan and southeast Asia. In the short-term, we don’t expect a trade war. China will give Trump enough to claim a “historic trade win” before the November elections, although US trade data will likely show the opposite thanks to a strong US$.

US-China trade tensions are unlikely to spill over into a trade war in the short-term, while risks on the Korean peninsula will continue to ease

Risk on the Korean peninsula will continue to ease whatever the outcome of talks between North Korea and the US. In the last year, Pyongyang has notched up three long-sought victories: intercontinental nuclear capacity; de facto recognition as a nuclear power (at least by the US); and bringing the US president to the negotiating table after six decades in which all prior US governments refused direct talks. A fourth big victory appears imminent, if Trump agrees to a formal recognition of the end of the Korean war at a June meeting in Singapore, which would lock in place the legitimacy of the North Korean regime. President Kim Jong-un is now focused on ending sanctions and supporting an economic recovery rather than sabre rattling. He’ll not give up nuclear weapons, so the question is what he might do – with Beijing’s approval – to save Trump’s face and allow sanctions to be eased.

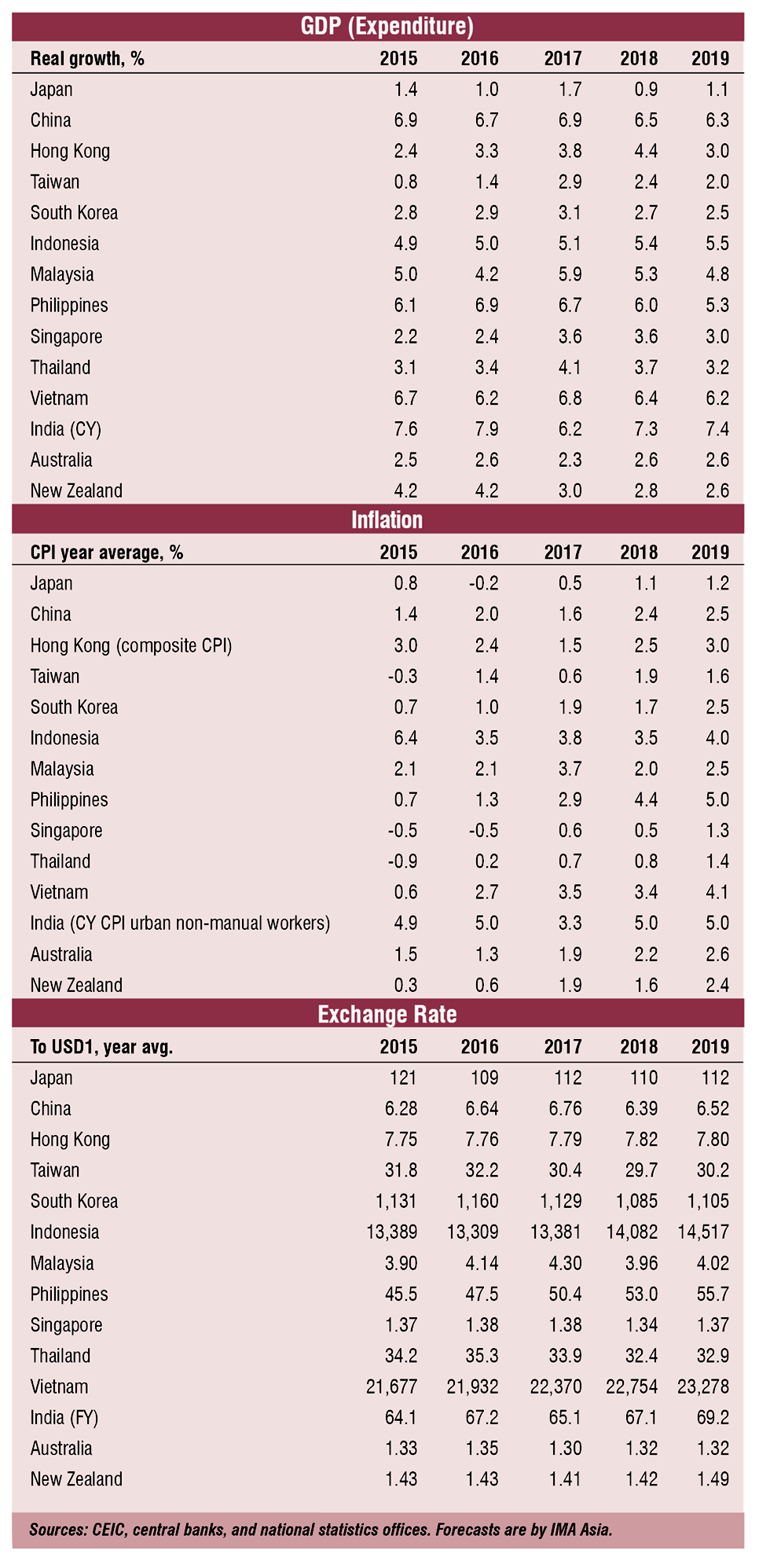

Our forecast theme for 2018 was for the region to see firm but moderating export growth with domestic demand set to play a more prominent role. So far, we appear to have under-estimated the strength of export demand, which through to April was running stronger than the rebound pace set in 2017 (see our Global Outlook). However, we expect a cooling in export growth to emerge in data for May and June and to continue through 2H’18 into 2019. As a result, our overall forecast for 2018 and 2019 is little changed from the one made in January. ASEAN is the only sub-region with a significant change, with growth for 2018 trimmed to 5% (from 5.3% in January) and to 4.8% for 2019 (prior 5%). Mostly, that recognises persistent weak growth in Indonesia and some cooling in overly-fast expansions in Vietnam and the Philippines.

The domestic demand side of our 2018 outlook remains intact, particularly in markets like Japan, China, India, the Philippines, and Vietnam. We expect Thailand to see a local demand revival this year, while Malaysia may get a boost from its new government. In our Global Outlook we argued that three of our 14 A/P currencies should be watched for currency falls, as the countries involved – the Philippines, Indonesia, and India – had rising current account deficits in a world increasingly wary of emerging market (EM) risk. That risk does not put them in the same category as Turkey and Argentina, which saw their currencies fall 15-20% on the US$ in May alone. Indeed, S&P released confirmation of a stable outlook for Indonesia at the end of May. The Asia three have strong foreign exchange reserves, and much lower foreign and public debt levels. As a result, modest policy interest rate rises should limit depreciations. Elsewhere, Asia saw strong rises on a weaker US$ over the last 12-18 months, particularly for China, Taiwan, South Korea, and Thailand. With the US$ returning to an appreciation phase on its trade weighted index from April, most of Asia’s strong currencies over the last 18 months are likely to give ground, as their respective interest rate differentials widen with the US.

Richard Martin is Managing Director, IMA Asia. He can be reached at richard.martin@imaasia.com

The Indian economy is recovering, but in an election year, it is politics that will remain the central focus

India is one year out from the 2019 general election in which PM Narendra Modi and the BJP will seek a second 5-year term. That election will mark two decades with four administrations that have all served full terms, including two changes in government, which is a remarkable statement of stability for any parliamentary democracy today. Such stability supports policy evolution and better growth. Mr Modi remains the 2019 favourite as he has done enough to sustain popular support. He will also continue to focus on winning over more state governments with the aim of gaining control over India’s upper house. Congress, the main opposition party, is weak but may regain ground by partnering with state-based opposition parties, a strategy that has delivered some success in the recent past. The BJP lost a few symbolically important by-polls across the country in recent weeks by unified oppositions, while in Karnataka the Congress kept the BJP out by allying with the local JD(S). However, the same approach is not easy to replicate at the national level where voters look for iconic leaders and an alliance proposition that is founded on more than just the desire to keep another party from winning.

GDP growth is accelerating, investment is firming up, and the early arrival of the monsoon bodes well for rural demand

In his first term, Mr Modi pushed through enough laws to show that he is serious about reform-driven growth (the bankruptcy law and the GST stand out). Yet the results are modest and some of the other challenges (reform to land and labour markets) have yet to be tackled. His first term was also marred by some mis-hits, such as demonetisation and increased protectionism. However, he will wrap up his first term with a start on labour market reform by amending the 1948 minimum wage act, which created a fragmented system (by industry and state) that only covered firms with 1,000+ staff. For the first time, the central government will set a floor wage by industry and all companies will be covered, with a big increase in penalties for breaches. This could have an impact on wage costs for both small and large companies.

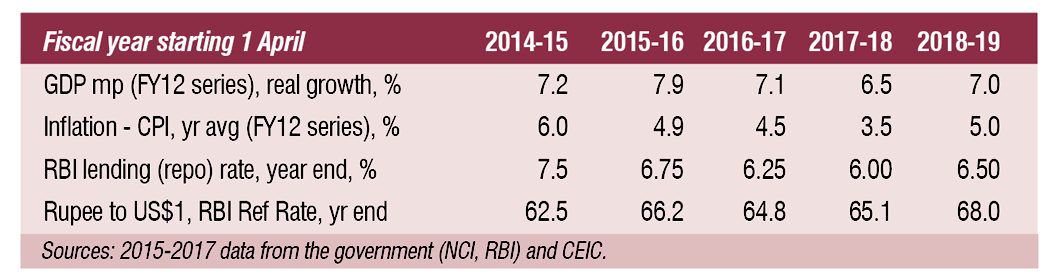

India’s economy is lifting after a slump to 6.2% growth in 2017 on the GDP expenditure measure, while growth on the industry GDP measure slipped to 6.1% on account of GST implementation and the drying up of bank credit. The March quarter saw GDP growth accelerate to 7.7%yoy as domestic demand rebounded by 10.1%yoy.

Real growth in consumer spending slipped to 5.7% last year from a decade average of 7.6%pa to 2016, as consumers struggled with demonetisation and the GST. With those problems fading, we expect a lift in growth this year. Vehicle sales were steady in April at 7.5% yoy, close to the FY18 average of 7.9%. 2-wheeler sales grew by 17% yoy against 14.8% in FY18 while commercial vehicle sales surged 76% in April against 20% yoy in FY18. Rural demand is also important and the early arrival of the southwest monsoon (May 29 in Kerala) with a forecast 54% chance of normal or better rainfall across the country, should help after below normal rain in 2017 and droughts in 2014 and 2015.

Calendar year 2017 witnessed a 4.5% yoy drop in fixed investment proposals but 2018 has started strongly with proposals worth Rs 2.3 trillion already in the pipeline in the January-March quarter. This is almost 60% of what was proposed in the entire year 2017. Capital goods production on the industrial production index was up 9%yoy in Q1’18 after rising 2.7% in full 2017. One of the drivers for this is the improvement in credit growth. Bank loans to the commercial sector were up 12%yoy in April from 5%yoy in April last year.

The rupee has dropped 5.5% against the dollar since January 2018 as markets are worried that higher oil prices will push up inflation and the trade deficit. We expect the RBI to use a mix of forex market interventions (it has large reserves) and rate hikes to limit the year average fall for the Rupee to 3-5%.